Last October,

if you might remember, I took a trip with the kids down to visit my mother in Suffolk. It's not my favourite place on earth, but on the upside I managed to convince my mother to make a day of it in London so we could make a visit to the Celts exhibition at the British Museum.

Over all I was a little disappointed with the exhibition, but I was interested in seeing it again once it got to Edinburgh in the new year, just to see if it was much different. It's a bit of a trek from here to get to Edinburgh, so I wasn't sure when we'd be able to manage it, but it turned out that our plans to go visit my family and friends down south weren't going to work out – schools in Scotland finished for the Spring break just as schools in England were returning from theirs and the timings just weren't going to align. So instead, seeing as Mr Seren had already booked time off from work, we decided to have a few days out, and Edinburgh was one of them.

We got there a little late in the day thanks to a slight detour (which meant we got to see the new Forth road bridge that's being built at the moment, and that was pretty cool), so by the time we'd parked up and got into the city centre it was well past lunchtime. It was nearly 3pm by the time we got to the museum, which didn't give us long to look around. Tom wasn't so keen to come and look at the Celts exhibition again, seeing as there was also a Lego "build it" thing on in the museum, so he and Mr Seren decided to do a bit of that before going off to look at the natural history stuff. Rosie decided to come with me so she could look at the shiny stuff again. She likes the artwork.

In London the exhibition cost £16.50 to get into, but in Edinburgh they're charging £10 for entrance (kids go free). The actual price is £9 but they've added on a pound extra for a "donation" to the museum, and while they do tell you that and ask if you want to make the donation, it's a bit cheeky to do that. Again, there's no photography in the exhibition which still pisses me off. I didn't bother trying to sneak pictures this time because there were way more members of staff around; it just wasn't going to happen.

Once we got in to the exhibition it was already very noticeably different. In London there was a three-minute slideshow as soon as you walked in, and while that would have been very informative, it clogged everything up from the get go. In Edinburgh we walked straight into a section with a few pieces on display that I think were intended to set the tone for the rest of the exhibition. They were a different selection from the ones chosen in London, in throughout the rest of the exhibition there were some pieces that were very noticeably missing – the bucket and flesh-hook I managed to snag pictures of in London, for one, along with a very impressive Gaulish statue of some dude with a big headdress. Those were the more obvious pieces I noticed missing and I'm sure there were others too. I noticed a few pieces I didn't think I'd seen before but I suspect that all in all there were some major artefacts that didn't make it to Edinburgh from the London exhibit.

That aside, I think the layout and flow of the Edinburgh exhibit is much better. The Gundestrup cauldron is on display in a room all by itself, and it's been set at a more sensible height so you can see all around it. The lighting is a little better, too, so it really becomes a feature all of its own rather than just one more shiny thing in a sea of shiny things.

There's a chariot (or replica of what the chariot would have looked like when it was fully intact) and goods on display that were recovered from a burial, and Rosie commented that she wasn't sure the people would be too happy to find all their stuff on display in a museum instead of in the ground where they left it. Wouldn't they want it to be left alone? she wondered. That's a perennial question in archaeology, I said. A lot of the time these things are dug up because they're going to be destroyed otherwise, so is it better to destroy them or try and recover them and preserve them so we can learn about the past? Rosie decided that perhaps the best thing would be to stop building stuff on top of important places like other people's graveyards and put the buildings somewhere else. I couldn't really argue with that, to be honest. But still, she loved looking at all the metalwork and jewellery, and we spent quite a bit of time looking for all the hidden faces and anthropomorphic features. When we got to the statue of Brigantia she was pretty excited and wondered if she was related to Brigid.

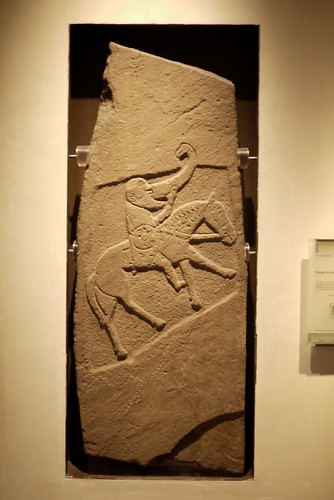

After we came out of the exhibition we met back up with Tom and Mr Seren and I decided I wanted to look at the "Early Settlers" section where all the early Scottish stuff is. We only had an hour left before closing by this point and I really didn't have time to look at everything I wanted to, but even so the place is amazing. One thing I noticed is that where the more well-known items had been taken for the Celts exhibit, they often replaced them with replicas, unlike in London. I thought that was a nice touch.

There were plenty of shiny things like the Pictish "plaques" from the Norrie's Law hoard (one of which was in the Celts exhibition):

In pictures you might think they'd make a nice pair of earrings, but they're way too big for that.

Silver hoards are pretty common in this period of Scotland's history because there wasn't much raw material available, so they had to rely on recycling silver instead. In some cases the hoards consist of Roman silver, which were presumably given to the local Picts, Britons or Gaels as bribes.

But it's not all about the shiny stuff, and that's one of the reasons I really wanted to go to the museum in the first place, because I wanted to see this – an almost perfectly preserved woollen Pictish hood:

Which was found in St Andrews parish (I presume that means the St Andrews in Fife, east coast of Scotland) and dates to some time between the 3rd-6th centuries CE.

There's also a hat, woven from hair moss, that dates a little earlier than the hood, around the first century CE. It was found at Newsteads, near the Scottish border:

And this is what the hair moss thread or twine looks like close up:

Things like this are what interest me most because it brings home the fact that we're not just dealing with something so nebulous as "a culture," but actual

people.

I mentioned in my post from the London museum that there were the "divination spoons" on display in the Celts exhibition, and they were on display again in Edinburgh with a note to say they may have been used for magical or "healing" purposes. Nobody really knows what they were used for, but I found a set on display in the main part of the museum that had been recovered from the east coast of Scotland:

There seems to be some deep politics surrounding these things, because while there's the pet theory that Miranda Green pushes about their being "divination spoons," which is reflected in how they're described down in London, Edinburgh chooses to simply describe them as "a pair of sacred spoons, possibly buried with a holy man:"

These ones are bronze, as you can probably tell, and they were recovered with a bronze dagger, too. They aren't as well preserved as the ones in the Celts exhibition, but if you look closely they have the same kind of markings – one spoon being quartered, and the other with a hole in it. People seem to get weirdly invested in the idea of their being used for divinatory purposes, but there really could be any number of other explanations. I can see

why divination has been suggested, but it bugs me that the idea gets treated as absolute truth by some.

Anyway. One last shiny thing before I finish off:

These are very late Bronze Age, and while the swords are set next to some moulds, I don't think they're the actual moulds that were used to cast them.

There's very little evidence for Bronze Age metal-working in Scotland, but a few sites have been found relatively recently that's changing what we know of the practice. I went to a lecture about one such place (just down the road from me, in fact, situated right on the coast) a few months ago and it was mentioned that the layout and orientation of the site had clear suggestions of ritual or religious purposes. The site, which is thought to have been very late Bronze Age in date, was surrounded by a number of palisades and the entrance was oriented to the south-east (very common for this period and into the Iron Age) with what appears to have been some sort of processional way leading into the main enclosure. One of the most interesting things that they found from the site is that the moulds were often transported across the Firth of Clyde so that they could be deposited at the foot of a major hillfort that dominated the area. This practice continued into the Iron Age, and it's thought that the burial of the moulds is possibly ritual in nature – perhaps an offering of some sort? It's no surprise that there seem to have been religious overtones to the production of metalwork, but it's fascinating to me, nonetheless.

Anyway, I think that's enough for now; I'll continue in another post with some more bits and pieces that piqued my interest another time.