Singing with Blackbirds: The Survival of Primal Celtic Shamanism in Later Folk-Tradition

Stuart A. Harris-Logan

Let's start with the blurb on the back of the book:

Singing with Blackbirds is an investigation of the survival of primal Celtic Shamanism in later folk-traditions of Gaelic speaking peoples. This is an insightful and intelligent work that brings together areas of study not normally combined.Going by this alone, it's obvious that this book has clear and lofty aims. I'll say right out, though, once you get into the nitty gritty of it all, those aims will probably end up leaving you with more questions than answers (and not in a good way). It certainly did me...

I'll admit that I have something of a bias against anything that claims to be "Celtic Shamanism," and to be fair to the author, he's well aware of some of the criticisms that are aimed towards the use of the label (or "shamanism" in general). So perhaps I'm predisposed to be skeptical of books like this, but I'd like to think that even if I'm not keen on principle I can at least give valid reasons for any criticisms I might have beyond some kind of knee-jerk reaction. I hope so. Harris-Logan mentions "encountering a lot of hostility from a number of groups which took exception to my research," so I'm sure it will come as no surprise to the author himself that there are those who might be critical (though I wouldn't say I'm especially hostile, personally...). Because of this, at the back of the book there's a section called "Apologia," where Harris-Logan gives a very useful outline of his reasons for using the term, and the crux of it boils down to this:

"Arguments against the use of 'shaman' and shamanism' as ethnological terms appear to be founded on the notion that they are not derived from a Celtic language. If we were to retrict its use merely to it's [sic] native culture, then only Tungusic shamans could be defined as such...

"Restricting our vocabulary in this way makes an exercise in intercultural comparison both awkward and limited. Without an umbrella term, how are we able to hold one technique up against the other? ...I need a term to compare the practices of the Kwakiutl hamatsa and the Irish gelta. I need a term to compare the Buryat shaman's and Cú Chulainn's visionary experiences. I need a term to compare the spirit dance with rituals found to be taking place in latter day Coll and Uist. In short, I need 'shamanism'." (p133)But I want to be clear that it's not simply the principle of using a loanword that I object to here. It's the fact that such a word describes a specific set of practices of a specific people, and I feel it's impossible to separate the original word from its culture and specific meaning within that culture. I feel it's wrong to try. Co-opting that word, adapting and generalising it to assume that the ritual practices of disparate are all one homogenous thing does a disservice to all of those practices, to my mind, especially when there are more accurate words from those cultures languages to describe them better.

On top of that, there's the fact that "shamanism" (in the popular sense) has been used to apply to a set of beliefs and practices that are highly problematic (see links, above). Not just "problematic," but mired in racism and rampant appropriation. It's unfortunate that Harris-Logan uses the very author responsible for kicking that all off – Michael Harner – along with at least one of Harner's students in order to try to prove the points he makes throughout the book, and this is something that certainly casts a negative over the whole book for me.

So there's the principle of the thing that I object to, yes. But it's also the fact that such an approach just doesn't hold up under any kind of academic scrutiny, and Harris-Logan himself is keen to emphasise that Celtic Studies has a lot to offer this kind of subject. The very problems I have with "core shamanism's" (as Harner himself calls it) approach in general underpin the approach Harris-Logan takes throughout the whole volume, as well: context is ignored, and comparative evidence is relied on heavily, even though the evidence comes from completely unrelated cultures and so have only limited bearing upon one another (more often than not). For instance, we're told that the Celts had totems and power animals, just like Native Americans do, even though he doesn't really define what these actually mean to Native Americans (or if they're even universal or exactly the same between tribes). The logic goes that totems are a thing somewhere in the world, therefore it follows that the exact same concept exists amongst the Celts because animals appear in a spiritual, similar-seeming context, too. Ergo, shamanism. And so it goes. What the evidence amongst the Celts – and amongst the different Celtic cultures themselves – suggests isn't considered.

In general, no matter which culture is being referenced, they're all treated as if they're talking about the same thing. On a very basic, broadly generalised level, there are similarities between many cultures, even those who never came into direct contact with one another, to be sure – we're all human, after all. But here, Harris-Logan draws on evidence from all over the world to show that shamanism is found in Celtic cultures, and at times it feels like he focuses more on non-Celtic cultures to prove a point than he does the actual Celtic cultures that we're supposed to be looking at.

Where there are clear relationships between cultures, they're treated as though they're one and the same, to the point where I'm not really sure if this book is supposed to be about "Celtic" Shamanism or "Gaelic" Shamanism. One of the people who contributed a glowing endorsement for the back cover seems to be similarly confused (referring only to "Gaelic Shamanism" despite the book's title), and I can only assume that this is presumably because it doesn't matter, because it all goes back to a primal (which seems to mean "universal") set of practices, anyway. (Which makes me wonder... why bother with slapping on a cultural label at all?)

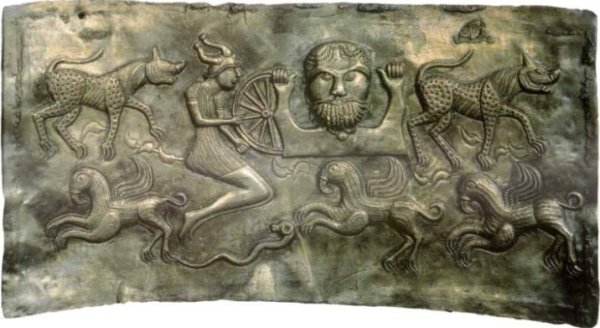

But let's get down to the nuts and bolts, not just the general approach. The evidence is often twisted to fit the point the author's trying to make, even when the evidence is very obviously lacking, and one of the worst examples of this is in Harris-Logan's attempt to prove that drumming – as an element of shamanic practice that's "a crucial technique to most shamanic cultures, a catalyst for the spirit journey..." (p27) was also a thing for the pre-Christian Celts. He acknowledges that there isn't any overt evidence for this – no archaeological evidence, nothing in iconography or myth that outright describes or shows ritualistic drumming – but he goes on to argue that the "wheel" iconography found in Gaulish depictions of religious art, like this one shown on the Gundestrup cauldron:

|

| Interior plate 'C' of the Gundestrup Cauldron. Source: Wikipedia |

Is really a drum (in spite of the fact that these wheels consistently have way more spokes than the "shamanic drums" he compares them to, which only have four – rather like some bodhrán designs, which are relatively modern in origin as instruments go). Obviously this leaves something of a hurdle for the Gaels, because the Gaulish evidence doesn't apply and drumming is never mentioned in any of the myths, so here he argues that drumming was such an obvious part of practice that it wasn't necessary to reference it overtly, and also points to examples where he argues that an oblique reference to a drum is being made – interpreting passages and names from Irish myth that refer to wheels as secretly referring to the shamanic drum (though why not just say it outright if it's something that's so obvious and pervasive a practice? If it's no great secret, why the secrecy?). The significance of all this, Harris-Logan argues, is that, "This may be suggestive of a shamanic spirit journey." (p31)

Ultimately, Harris-Logan concludes:

"With the weight of this evidence it is impossible to discount the theory that the early Celts possessed drums. I agree with Trevarthen's note that the drum is a very primitive instrument possessed by most cultures across the globe (whether operating within a shamanic mode of perception or not), and it would be surprising if early Celtic tribes did not possess this basic instrument." (p33)I find this whole argument to be extremely tenuous at best.

The meaning and etymology of certain words are discussed at several points, but actual meanings are often ignored in favour of personal interpretations that have no factual basis. Take "imbas" for example, which eDIL defines as "great knowledge; poetic talent, inspiration; fore-knowledge; magic lore," and breaks it down as coming from two words, "imb-ḟiuss or imb-ḟess." (Note: the wee dots above the 'f' in both examples there indicates lenition, which effectively kills the 'f' sound altogether). Harris-Logan, on the other hand, asserts that:

"The etymology of the term imbas (often translated as 'inspired' or 'poetic knowledge') is commonly given as 'in the hands' im (in) + bas (hands). It is also possible, though, that bás may have been intended instead of bas. If this is true, then a more correct translation would be 'in death' – supporting the shamanic mode of perception surviving in the modern Scots Gaelic language." (p48)Although I'd still disagree with his conclusions here, I wouldn't have as much of a problem with assertions like this if the author was clear that this was either his own opinion, or could back it up with citations and a discussion of why he feels the eDIL etymology is wrong and why he discounts it. Phrases like "commonly given" don't help here, either, in trying to suggest this is a firm and accepted fact when it isn't.

In some cases, to be fair, he does make his linguistic speculations (or acceptance of other authors' speculations) more clear – such as the speculation that dán may be more accurately translated as "co-creative power" or even "shamanism" rather than "skill, art, gift, fate," (though I still disagree with his argument here). Elsewhere, however, he makes more spurious claims, like his mention of the dance called "cailleach an dùdain" (described by Carmichael in the Carmina Gadelica, in reference to a Michaelmas tradition) as evidence of birds having ritual significance in Gaelic "shamanic" practice. This is based on his translating the phrase to mean 'dance of the smoky owl,' which I can only assume is his own interpretation because it really means 'The Old Woman of the Mill-Dust.' Cailleach-oidhche means "owl," which is probably where he's coming from, but there's absolutely no supporting evidence for his interpretation here, and again he's stating something as fact when it's far from being the case. Things like this undermines any actual points that are being made because he's simply stretching the evidence to fit the picture as he wants it to.

The book is split into three main sections, the first section being titled "Druids and Drums: The Instruments of Ecstasy," and the second "Gaining Possession of a Sacrality." These two sections are primarily devoted to illustrating Harris-Logan's view of how the Celts were obviously a "shamanic" culture, based on comparative sources from all over the world. In the third section of the book – which is titled "A Shaman in the Gàidhealtachd?" – the majority of evidence is drawn from the Carmina Gadelica, with various prayers being given to support Harris-Logan's assertion that shamanism is evidenced in later folklore. My problem here is that no consideration is given to the context of the prayers – who said them, why, how – or how old they might be, what influences there might be evident in them, or whether or not Carmichael might have helped to "improve" the verses, to support or detract from the point that's being made. A prayer for justice (Ora Ceartas) is given, for example (along with several other prayers of varying purpose), but after the previous two sections, which go to great lengths to show that shamans were specialists of their arts – it wasn't something that everyone did, or was open to anyone who wanted to know more; the rituals and arts of the shaman were the purview and privilege of the shamans alone – the third chapter leaves me wondering how prayers like this (which were said by anyone in a situation where such a prayer was needed) are evidence of shamanism? If the rituals and specialist knowledge of shamans was known only to initiates, how and why did shamanism become more "public" in the Gàidhealtachd? This isn't addressed by Harris-Logan at all.

None of the prayers, or the myths that are discussed throughout the book, are viewed critically at all. At several points in the book the druid Mug Ruith is used to illustrate evidence of "shamanism," but the fact that the stories involve Mug Ruith are quite late, and Mug Ruith himself is presented as a "druid" through a very Christian lens, is ignored (see, for example, the discussion of Mug Ruith in Fiery Shapes). Harris-Logan himself argues for a more academic approach in dealing with the material, but over all I can't help but feel that he fails to illustrate one.

I can't say I found everything to be a total negative, though, and I don't want to sound like I'm totally hating on the book. In spite of my total disagreement with the majority of his interpretations and the over all point of the book, some of it was interesting and he draws on a diverse amount of evidence to support his arguments. As a fluent Gaelic speaker, he also gives his own translations of some of the prayers given in the Carmina Gadelica, and while they don't seem to be wildly different from Carmichael's own translations – just a few tweaks here and there – they do at least seem reliable (though I'll note that I'm not a fluent-speaker, by any stretch!) and are a little more up to date in language.

I also appreciated his discussion of how Gaelic works – the way only things that are integral to us, like family, or body parts, are spoken of with "possessive" phrases. To say "my hand" you say "mo lamh," which is literally "my" (mo) "hand" (lamh), but to say "my husband," or "my wife" you say "an duine agam," which literally means "the man (husband) that is at me." This isn't the first time I've seen such a thing discussed, but I've not really seen it discussed in any detail, and it's refreshing to read about this stuff from fluent speaker.

Again, however, there's a problem with some of the stuff that interested me because it's unreferenced and so I'm not sure how reliable it is. In particular, there's a note that tells the reader that the phrase ri traghadh 's ri lionadh, "With the ebb and with the flow" is "the name given to a traditional form of Gaelic singing." I recognise the phrase from a prayer that Carmichael gives in Volume II of the Carmina Gadelica (it's a prayer that we outlined in our Children and Family in Gaelic Polytheism article on the Gaol Naofa website, and expanded on as well), but I've never heard of it being applied to a form of singing and can't find anything to back this up. But if this is the case I'd certainly be interested to know more, especially if it sheds light on the prayer Carmichael gave, which is simply titled "Fuigheal/Fragment."

Ultimately, there just aren't enough interesting tidbits to make up for all of the problems I find with the book over all, and I couldn't recommend it. I think you're better off going straight to the source, so to speak, getting hold of the Carmina Gadelica and reading the myths yourself. Learn about the hisory and society these things come from, as much as you can. Context is important.