One of the first things I did when we moved into the house we live in now – back in 2008 – was do all the nesting, the decorating, and the making the place ours. A lot of that involved a painting and wallpapering, getting out in the garden to give it a good overhaul, and taking the opportunity to splurge on furniture, and so on. The usual stuff.

The layout of the house meant that we could also finally find a decent spot for a huge bookshelf Mr Seren took a fancy to some years ago, when we moved into our first house together. It's an antique camel cart that's been adapted into a bookshelf, and it probably quite literally weighs a ton, and two houses later we finally had a place for it to sit, rather than having it dumped somewhere unceremoniously (in the porch of all places, in our previous house). We set it up in the kitchen-dining room, and I decided to dedicate one of the shelves as my shrine area. As the heart of the house, it seemed more appropriate to set it up in the kitchen than on the mantlepiece of the fireplace in the living room (and in a practical sense, the shelf was more out of the way from sticky fingers than the mantlepiece, so nothing would get broken).

Initially, I didn't have much to put on the shelf, so it looked quite sparse. I set it up like this:

But I found pretty quickly that most of the plants needed more light than the space could offer them, so a bit of rejigging was necessary (a few more unpacked boxes brought up more things to add, too). Over the years, though, I added more and more bits and pieces – gifts that were sent by wonderful friends, things I found as I went out and about, and some pieces I made myself as the fancy took me. Some of those ended up outside too, as I set up a shrine area up by the rowan tree I planted, with a 'pond,' a small cairn dedicated to my ancestors, space for offerings, some plants that relate to the festivals or my ancestors, some decorative pieces, and so on.

But inside, on my shelf, things have become rather cluttered over the years, and I've now ended up with this:

The plate at the front there is for offerings, and I've replaced the plaque from my granddad, that I originally put on there, because I realised wasn't sure what metal it's made from. I decided to remove it in case there was any iron in it – it seemed bad form. So I've replaced it with a small matchbox that used to belong to my grandparents, and which sat on a table of stuff for years. I loved the decoration on it as a kid, so when I found out that mum was going to dump it at a charity shop on my last visit to hers, I decided to 'rescue' it. There's the fossil I found one Midsummer at the beach, the hobhouse and the 'bile' candle holder I made, the Cryptic Crow that takes pride of place and represents Badb, and some protective charms like amber, red coral, rowan berries, and the rowan charms I've made over the years (that are more decorative than the ones I usually do):

I put the skull lights up for Samhainn one year. The kids insisted they should stay up.

You can't quite see it in the full-shelf picture, but just next to the dealbh Brìde we made this year, Rosie's put another one that she made all by herself out of pipe cleaner, sticky tape, feathers and some decorative charms that 'accidentally' came off some pen lids. Things keep mysteriously appearing on the shelf now that Rosie's tall enough to reach, and so long as things don't mysteriously disappear, that's OK by me. Occasionally she rearranges the cows because apparently they're busy having adventures, which are played out on the shelf, and if the kids had their way any empty space would would be overrun with rocks and shells from the beach. As it is, we've reached a compromise on that and their collection lives on one of the shelves below.

Last Samhainn I had the urge to make some more stuff for the shelf, and given the ancestral theme for the festival I'd been thinking about the kind of thing I could do that tied in with that, but in a way that fitted with the kind of iconography you find throughout the ages. A way of fitting in with the whole continuum, as it were. So I decided on a triskele from Newgrange, a picture of which (from the actual place) Rosie decided to have on her Wall of Wonder in her room:

So it's a little bespoke, but my little helper (Rosie) insisted it was finished the way it is. As I traced the swirls free-hand it provided a good focus for meditation and contemplation about things, and it got me in the mood for the festivities.

In my regular observances I only really make offerings at the shelf when the weather isn't suitable for doing that outdoors – I prefer to make offerings outside – although Rosie's taken to putting flowers like dandelions or daisies up there for Brìde. For festivals in particular I tend to perform the bulk of my observances at the shelf, since the focus of them is on the home and the household, but I also like to go outside then as well. It feeds kind of politer, going outside to greet the spirits of the place and make offerings of peace to them on their own turf, as it were, and I prefer to look for signs and omens outside than taking ogham (though I occasionally do that too). On a daily basis I prefer to look outside and see what the day might bring as I take a moment to offer up a prayer in the morning, rather than go to the shelf, although longer observances and saining are often done at the shelf.

A shrine isn't necessary, to me, but I do think it can help as a focus. It helps me articulate my beliefs and my relationship with the world around me. It's a microcosm, in that sense, and maintaining it, adding to it, helps to express how things change as well – seasonally, with decorations that reflect the time of year or the festival, and on a broader scale, too.

Pages

▼

Monday, 24 March 2014

Friday, 21 March 2014

An Cailleach Bheara

I've posted a link to this short film before, but it's well worth another watch! 'Tis the season, and all...

Soon the Cailleach Bheur will make her lament as she gives up and admits defeat in trying to hold back the onslaught of Spring. As she throws down her wand, she shouts out:

| ‘Dh’ fhag e mhan mi, dh’ fhag e ‘n ard mi Dh’ fhag e eadar mo dha lamh mi, Dh’ fhag e bial mi, dh’ fhag e cul mi, Dh’ fha e eadar mo dha shul mi. |

It escaped me below, it escaped me above. It escaped me between my two hands, It escaped me before, it escaped me behind, It escaped me between my two eyes. | |

Dh’ fhag e shios mi, dh’ fhag e shuas mi, Dh’ fhag e eadar mo dha chluas mi, Dh’ fhag e thall mi, dh’ fhag e bhos mi, Dh’ fhag e eadar mo dha chos mi. |

It escaped me down, it escaped me up, It escaped me between my two ears, It escaped me thither, it escaped me hither, It escaped me between my two feet. | |

Thilg mi ‘n slacan druidh donai, Am bun preis crin cruaidh conuis. Far nach fas fionn no foinnidh, Ach fracan froinnidh feurach.’ |

I threw my druidic evil wand. Into the base of a withered hard whin bush, Where shall not grow 'fionn' nor 'fionnidh,' But fragments of grassy 'froinnidh.' |

While the Irish An Cailleach Bheara doesn't have such firm associations with the seasons as the Scottish An Cailleach Bheur does, there are some hints. Cairn T, at Loughcrew (or Sliabh na Caillí) is thought to have an equinoctial alignment:

The light of the equinox sunrise illuminates the back chamber of the Cairn T at the Loughcrew complex, lighting up carvings that are thought to have astronomical meanings. Near to Cairn T is the Hag's Chair, and she is said to have created the tomb by accidentally dropping a pile of stones from her apron. But of course, in spite of her associations with the place today, we can't really say when the Cailleach came to be associated with the place – certainly not until after Christianity, when the word 'cailleach' came into the Irish language – or if her associations are meant to tie in with the equinoctial alignment. The coincidence with the Scottish Là na Cailliche is tantalising, however.

It does seem like she has other, older names as well, which offer further (possible) seasonal associations. In The Lament of the Old Woman of Beare, she calls herself Buí, who is referred to as a wife of Lugh in other sources, and is said to have been buried at Knowth (Cnogba). In the Dindshenchas of Nás (another of Lugh's wives) she is mentioned again, along with Tailtiu, so one wonders if she has an association with Lúnasa, which were often held at places that are thought to have been the burial place of supernatural women or goddesses who were married to Lugh, or otherwise associated with him? The Dindshenchas of Nás seems to hint that this was the case, since it mentions games and gatherings.

Another Dindshenchas, Lia Nothain, refers to two sisters, Nothain and Sentuinne, both of whom are "Old Women" and Sentuinne itself means "Old Woman" just as "Cailleach" can. The Dindshenchas associates them with May-day, suggesting further seasonal associations:

Nothain (was) an old woman [cailleach] of Connaught, and from the time she was born her face never fell on a field, and her thrice fifty years were complete. Her sister once went to have speech with her. Sentuinne (” Old Woman”) was her name: her husband was Sess Srafais, and Senbachlach (“Old-Churl”) was another name for him. Hence said the poet:

Sentuinne and Senbachlach,

A seis srofais be their withered hair!

If they adore not God’s Son

They get not their chief benefit.

From Berre, then, they went to her to bring her on a plain on May-day. When she beheld the great plain, she was unable to go back from it, and she planted a stone (lia) there in the ground, and struck her head against it and….and was dead. ” It will be my requiem….I plant it for sake of my name.” Whence Lia Nothan (“Nothan’s Stone”).

Nothain, daughter of Conmar the fair,

A hard old woman of Connaught,

In the month of May, glory of battle,

She found the high stone.

The association with Berre (Beare), just as Buí is associated with that place, suggests that they are probably one and the same. So there are some hints and bits of seasonal lore that may be associated with An Cailleach Bheara. It's guesswork, for sure, but I thought it's worth putting out there to ponder.

Tuesday, 18 March 2014

St Patrick's Day, with much wailing and gnashing of teeth

As the sound of much internet anguish and wailing and gnashing of teeth over St Patrick's Day recedes, we ease into Sheelah's Day...

I wrote a bit about it last year and put together some pointers to the references I'd found about it, and that's about as much as there is to go on, I think; I've found some additional references to it, but it's only ever a passing mention of the day that doesn't really add to anything. Just like Là na Caillich – which is what I tend to focus on at this time of year – Sheelah's Day seems to mark an official end to the winter storms, and thus marks the official beginning of Spring.

For many, according to the sources, it's also traditionally a day of nursing a hangover or partaking in a hair of the dog after yesterday's celebrations and revelry. For some of us today, it's pretty much a similar feeling, but instead of the after-effects of overdosing on alcohol, there's a hangover of frustration, of having had our fill of the ignorance and "alternative history" that abounds at this time of year. As much as anyone might write about how the snakes-don't-equal-druids, and that Patrick isn't responsible for mass genocide of the druids, pagans, or anyone else... there's always a depressing amount of wailing about it anyway. Here's the first one I saw yesterday:

Which... Since when has "driving out" meant "mass murder"? I mean, really.

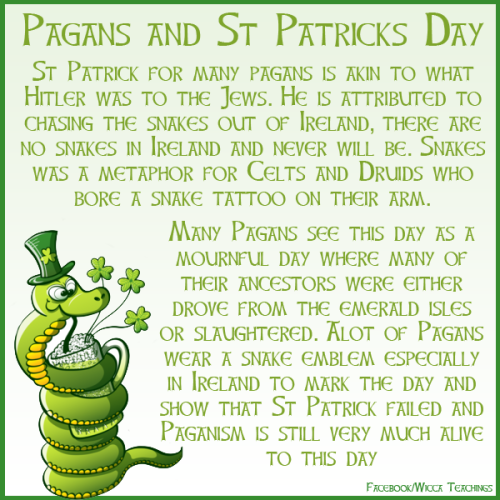

But anyway, here's (arguably) an even better one:

To be honest, this one's so condensed with bullshit (and an impressively immediate Godwin, to boot) that I have to point to Poe's law here... But I'm pretty sure the snake tattoo thing comes from Marian Zimmer Bradley's Mists of Avalon, right? It's been a while since I read it, but I'm pretty sure the male druids wore serpent tattoos in that. Although it's not the first time Mists has been held up as a factual story, is it?

The problem with this kind of thing is that – aside from the fact that it's so painfully inaccurate on just about every level that I almost want to cry – it's nigh impossible to counter. Saying "That never actually happened" prompts replies of "Prove it," but it's very difficult to prove the absence of something because by it's nature, there's nothing there to show as evidence. It's difficult to point to the absence of mass graves in the archaeological record. It's difficult to point out the absence of documentation on the matter, but pointing that out usually garners the kind of response that there was a conspiracy to cover that kind of thing up, because hey, "History is written by the victors," or variations along those lines.

We can disagree any amount. We can point to more accurate resources that show that the snake story is nothing more than that: A story. It's really nothing more than a stock motif, a miracle of a kind that many saints, heroes, and even gods before them are said to have performed. So we can even muse on the fact that stories of this type have their roots in paganism, and isn't that kind of ironic considering the fact that so many pagans are keen to believe that it's evidence of paganism's oppression?

But it often falls on wilfully deaf ears because the fact remains that some people want the illusion, the fantasy of oppression. People seem to want to believe that Patrick is responsible for the genocide of the druids and pagans. In spite of the fact that Christianity came to Ireland before Patrick did, and pre-Christian beliefs persisted well beyond Patrick's mission, people just want to believe their own narrative. There's no amount of evidence that can convince those people otherwise because they don't want to hear it in the first place, and it's embarrassing and cringeworthy to see memes like the ones above fly around at this time of year that perpetuate this kind of thing. Even worse, I think, are the people who recognise that there's no real truth to these claims, but choose to observe it as a day of "mourning" anyway. Mostly, it seems, because Christianity happened at all, And That's Bad.

Really, it's insulting. And offensive.

The reality is, Christianity happened. It arrived and spread peacefully in Ireland, and our Irish ancestors adopted it willingly – certainly not at the edge of a sword. There were no horrendous massacres of pagans who refused to convert, and the pagan Irish didn't find Christianity to be such a threat that they persecuted early Christians, either. So peaceful was the whole process that – as Gorm pointed out last week – Ireland's Christians had to come up with other ways to martyr themselves to the cause.

But it's always Patrick that's the focus of all this misplaced outrage, in spite of the fact that those same people who are so angry about him don't really know anything about him in the first place. Nowhere in the works of the saint himself, or in the later myths, legends and hagiographies (saint's lives) is he shown as a perpetrator of mass genocide. If he was that successful as a genocidal maniac, there would hardly be so many stories of him having miracle smack-downs with druids, would there? He's hardly the kind of guy who was all about sunshine and rainbows, either, but still. Anything he does – especially in the later sources – has more to do with showing Patrick in a way the writers wanted him to look, framing him in a way that people would understand, or that would get the message the writers wanted to convey across. It has very little to do with anything Patrick actually did during his life; the way the later stories portray him – as a warrior priest, a no-bullshit-purveyor-of-miracles-against-druids kind of guy – is at odds with the way Patrick portrays himself in his own words. Sure, Patrick wants to make himself look good, but the later sources are more concerned with making Patrick look powerful, to justify the authority of Armagh as the ecclesiastical centre of Ireland. Kildare did the same with Brigid.

But regardless of the things that Patrick did or didn't do, no one ever points the finger of outrage at those ancestors who converted, though, do they? Is the thought that they chose their own way – as we've done today, as pagans and polytheists of one stripe or another – so hard to reconcile that we need an imaginary scapegoat instead? If that's the case, then it's a weird kind of fundamentalism when people, many of whom claim to venerate those same ancestors, choose to accept a fantasy rather than come to terms with the fact that times changed in a way they don't want to fathom. It's hardly respectful to those ancestors, and it's hypocritical to demand respect for one's own beliefs when one fails to respect others. Clinging to a fantasy does nobody any favours.

Reliable resources on Patrick and Ireland's conversion:

Dáibhí Ó Cróinín: Early Medieval Ireland 400-1200

John Koch: Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia

Bernhard Maier: The Celts: A History from Earliest Times to the Present

Alexander Krappe: St Patrick and the Snakes

I wrote a bit about it last year and put together some pointers to the references I'd found about it, and that's about as much as there is to go on, I think; I've found some additional references to it, but it's only ever a passing mention of the day that doesn't really add to anything. Just like Là na Caillich – which is what I tend to focus on at this time of year – Sheelah's Day seems to mark an official end to the winter storms, and thus marks the official beginning of Spring.

For many, according to the sources, it's also traditionally a day of nursing a hangover or partaking in a hair of the dog after yesterday's celebrations and revelry. For some of us today, it's pretty much a similar feeling, but instead of the after-effects of overdosing on alcohol, there's a hangover of frustration, of having had our fill of the ignorance and "alternative history" that abounds at this time of year. As much as anyone might write about how the snakes-don't-equal-druids, and that Patrick isn't responsible for mass genocide of the druids, pagans, or anyone else... there's always a depressing amount of wailing about it anyway. Here's the first one I saw yesterday:

Which... Since when has "driving out" meant "mass murder"? I mean, really.

But anyway, here's (arguably) an even better one:

To be honest, this one's so condensed with bullshit (and an impressively immediate Godwin, to boot) that I have to point to Poe's law here... But I'm pretty sure the snake tattoo thing comes from Marian Zimmer Bradley's Mists of Avalon, right? It's been a while since I read it, but I'm pretty sure the male druids wore serpent tattoos in that. Although it's not the first time Mists has been held up as a factual story, is it?

The problem with this kind of thing is that – aside from the fact that it's so painfully inaccurate on just about every level that I almost want to cry – it's nigh impossible to counter. Saying "That never actually happened" prompts replies of "Prove it," but it's very difficult to prove the absence of something because by it's nature, there's nothing there to show as evidence. It's difficult to point to the absence of mass graves in the archaeological record. It's difficult to point out the absence of documentation on the matter, but pointing that out usually garners the kind of response that there was a conspiracy to cover that kind of thing up, because hey, "History is written by the victors," or variations along those lines.

We can disagree any amount. We can point to more accurate resources that show that the snake story is nothing more than that: A story. It's really nothing more than a stock motif, a miracle of a kind that many saints, heroes, and even gods before them are said to have performed. So we can even muse on the fact that stories of this type have their roots in paganism, and isn't that kind of ironic considering the fact that so many pagans are keen to believe that it's evidence of paganism's oppression?

But it often falls on wilfully deaf ears because the fact remains that some people want the illusion, the fantasy of oppression. People seem to want to believe that Patrick is responsible for the genocide of the druids and pagans. In spite of the fact that Christianity came to Ireland before Patrick did, and pre-Christian beliefs persisted well beyond Patrick's mission, people just want to believe their own narrative. There's no amount of evidence that can convince those people otherwise because they don't want to hear it in the first place, and it's embarrassing and cringeworthy to see memes like the ones above fly around at this time of year that perpetuate this kind of thing. Even worse, I think, are the people who recognise that there's no real truth to these claims, but choose to observe it as a day of "mourning" anyway. Mostly, it seems, because Christianity happened at all, And That's Bad.

Really, it's insulting. And offensive.

The reality is, Christianity happened. It arrived and spread peacefully in Ireland, and our Irish ancestors adopted it willingly – certainly not at the edge of a sword. There were no horrendous massacres of pagans who refused to convert, and the pagan Irish didn't find Christianity to be such a threat that they persecuted early Christians, either. So peaceful was the whole process that – as Gorm pointed out last week – Ireland's Christians had to come up with other ways to martyr themselves to the cause.

But it's always Patrick that's the focus of all this misplaced outrage, in spite of the fact that those same people who are so angry about him don't really know anything about him in the first place. Nowhere in the works of the saint himself, or in the later myths, legends and hagiographies (saint's lives) is he shown as a perpetrator of mass genocide. If he was that successful as a genocidal maniac, there would hardly be so many stories of him having miracle smack-downs with druids, would there? He's hardly the kind of guy who was all about sunshine and rainbows, either, but still. Anything he does – especially in the later sources – has more to do with showing Patrick in a way the writers wanted him to look, framing him in a way that people would understand, or that would get the message the writers wanted to convey across. It has very little to do with anything Patrick actually did during his life; the way the later stories portray him – as a warrior priest, a no-bullshit-purveyor-of-miracles-against-druids kind of guy – is at odds with the way Patrick portrays himself in his own words. Sure, Patrick wants to make himself look good, but the later sources are more concerned with making Patrick look powerful, to justify the authority of Armagh as the ecclesiastical centre of Ireland. Kildare did the same with Brigid.

But regardless of the things that Patrick did or didn't do, no one ever points the finger of outrage at those ancestors who converted, though, do they? Is the thought that they chose their own way – as we've done today, as pagans and polytheists of one stripe or another – so hard to reconcile that we need an imaginary scapegoat instead? If that's the case, then it's a weird kind of fundamentalism when people, many of whom claim to venerate those same ancestors, choose to accept a fantasy rather than come to terms with the fact that times changed in a way they don't want to fathom. It's hardly respectful to those ancestors, and it's hypocritical to demand respect for one's own beliefs when one fails to respect others. Clinging to a fantasy does nobody any favours.

Reliable resources on Patrick and Ireland's conversion:

Dáibhí Ó Cróinín: Early Medieval Ireland 400-1200

John Koch: Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia

Bernhard Maier: The Celts: A History from Earliest Times to the Present

Alexander Krappe: St Patrick and the Snakes

Wednesday, 12 March 2014

Youtube! Videos! Article!

As you might have seen with the announcement over at the Gaol Naofa site, we now have a new Youtube channel with a couple of videos already uploaded to start us off. The first is titled St. Patrick's Day (or, "What's Wrong with Saint Patrick's Day?"):

And it takes a look at the awful stereotypes that are often associated with the day (and people's perceptions of Irishness). The second video, Pagans, Polytheists, and St. Patrick's Day, deals with the misconceptions that are often trotted out at this time year – Snakes! Druids! Persecution! Oh my:

We also take a look at what the day means to us as Gaelic Polytheists, and how we might observe it.

These videos are the start of a series on the festival year in the Gaelic calendar, from a Gaelic Polytheist perspective, and we'll be putting up more for the other festivals in due course. Our long term plans include videos on other subjects, too (and if there's anything you'd like to see, feel free to leave a comment), and we also have some playlists on the channel that cover subjects like music, folklore, festivals, language, and history, which we think will be of interest.

Sionnach Gorm from Three Shouts on a Hilltop has weighed in on the St Patrick's Day issue as well, with a fantastic piece that goes nicely with the videos we've done:

Finally, because it's that time of year and it's a tradition now...

It's Paddy, not Patty.

And it takes a look at the awful stereotypes that are often associated with the day (and people's perceptions of Irishness). The second video, Pagans, Polytheists, and St. Patrick's Day, deals with the misconceptions that are often trotted out at this time year – Snakes! Druids! Persecution! Oh my:

)

We also take a look at what the day means to us as Gaelic Polytheists, and how we might observe it.

These videos are the start of a series on the festival year in the Gaelic calendar, from a Gaelic Polytheist perspective, and we'll be putting up more for the other festivals in due course. Our long term plans include videos on other subjects, too (and if there's anything you'd like to see, feel free to leave a comment), and we also have some playlists on the channel that cover subjects like music, folklore, festivals, language, and history, which we think will be of interest.

Sionnach Gorm from Three Shouts on a Hilltop has weighed in on the St Patrick's Day issue as well, with a fantastic piece that goes nicely with the videos we've done:

Mythically, at least, Pádraig and later saints subsumed the role of the warrior-elite heroes in the popular imagination. By replacing chieftains and druids with Christian saints possessed of miraculous powers, early Christian mythology carried on the patterns of the polytheistic originals they replaced. The mystical, and not the physical, would be the lynchpin in the conquest of the mythic landscape; a trope which is common enough that it appears in the Mythological Cycle, among others. While not unique to Irish hagiography, this is something that occurs repeatedly in the Irish lore. The supremacy of a figure like Patrick over that of the Druids (the most common representative of the Pagan past) is not based on his moral character, but on his supernatural abilities. This is a pattern which is discernible in other hagiographies, particularly that of St. Brigid of Kildare and St. Columba.That's up on the Gaol Naofa website, and many thanks go to Gorm for writing it, and to everyone who helped with the brainstorming, tweaking and proofing for the videos. In particular, thanks as always go to Kathryn and Treasa for their hard work.

Finally, because it's that time of year and it's a tradition now...

It's Paddy, not Patty.